Watch the documentary.

The term "grief" usually refers to a feeling of disgust, repulsion, or intense aversion towards something. When used in the context of "dying of grief" after an expropriation, it can suggest an extremely negative emotional state or even an affliction so intense that it contributes to the deterioration of the affected person's physical or emotional health.

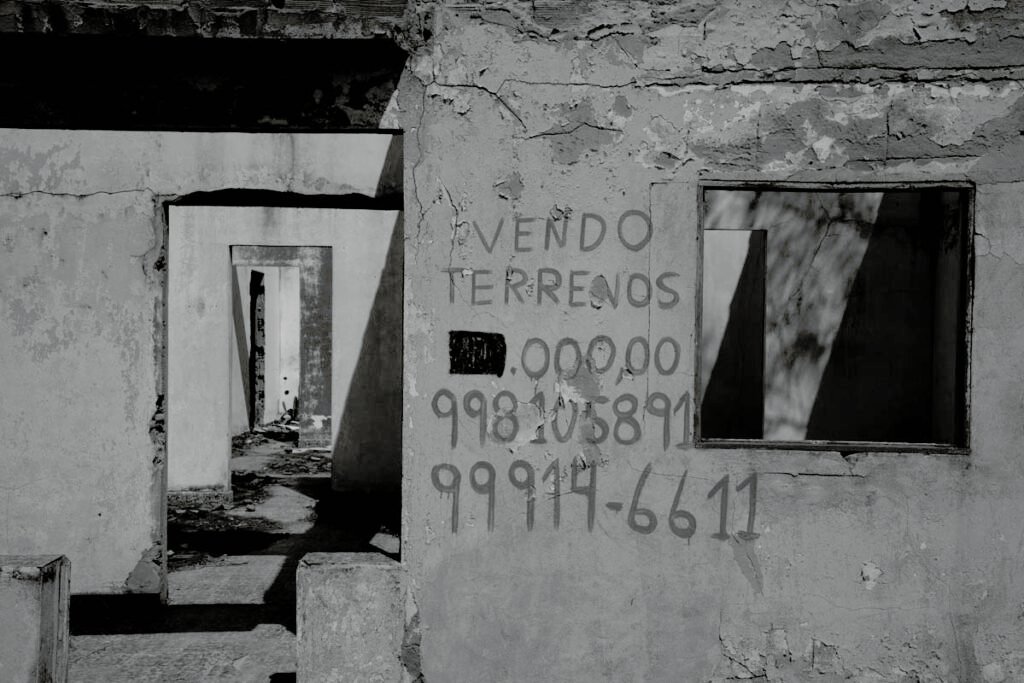

Farmers from the V District of São João da Barra, Since the morning of April 19, 2017, around 100 farmers from the Açu region in the municipality of São João da Barra-RJ, have been fighting to take back their land, which was confiscated by the Sergio Cabral government and Eike Batista’s EBX Group during the camp organized by Asprim in 2017. Pablo Vergara ©.

___ Summary

The project “Açu dos desgostos” is a multimedia narrative documentary highlighting the socio-environmental impacts of Brazil’s largest private port, the Port of Açu. The construction of the Port of Açu mega-enterprise left 400 small-scale farmers without their land, which was unjustly confiscated by the former billionaire Eike Batista, who later negotiated it with the private equity fund “EIG Global Partners” represented by Prumo Logística. The farmers received no compensation from the state. This led to unprecedented violence in the region. In addition, the environmental impact generated by the port destroyed regional ecosystems known as the “Restinga”, salinized arable land and accelerated coastal erosion processes. The restructuring of the port following the global financial crisis led to a reconsideration of its operations. Today, the port has turned its attention to the oil and gas sector and energy production, mainly through gas-fired thermal power stations, far from its initial project, a sizeable industrial-port complex envisioned by former tycoon Eike Batista.

Communities of small farmers have been organizing since the port was built in 2012, starting with the occupation of confiscated land. In the photo, the camp was organized in 2017, where around 300 farmers gathered to draw the attention of the public authorities. Pablo Vergara © 2017.

The international crises of the capitalist rental markets (2008) impacted Brazil in mid-2014-2016, which changed the nature of the project. The current objective is to transform the port of Açu into the largest gas-fired thermoelectric park in Latin America, with a production capacity of 3 GW of power.

The two thermal power plants will generate enough energy to supply 14 million homes, equivalent to the residential consumption of Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and Espírito Santo. The problems with the new production “turnaround” are human rights, which the big corporations have once again violated since the high-voltage power lines were built on land that was confiscated from small farmers and has still not been adequately compensated, which is still a political-legal dispute with no litigious resolution. The high-voltage power lines also pass through areas of coastal vegetation and local flora and fauna, increasing the region’s environmental conflict. Lastly, the emission of gases produced by the thermoelectric park accelerates climate change in the area, according to the farmers, who report acid rain on their plantations, as well as radical changes in temperature due to the greenhouse effect.

___ Introduction

The “Açu dos Desgostos” project is a multimedia narrative documentary highlighting the socio-environmental impacts of Brazil’s largest private port, the Port of Açu. Initially, the Port of Açu (2008) was designed as a sizeable industrial-port complex (CIPA), including the world’s longest mining pipeline (328 km) for extracting minerals, along with various offshore ventures in the oil and gas industry, as well as steel and metallurgical companies that would be built on the site. The initial project, which promised a lot of progress in the region, quickly ran out of steam, and the accelerated changes in international markets brought several adjustments to the production processes, which were initially focused on extracting commodities and supporting the oil and gas industry. The initial project had to reconfigure its operations at the Port of Açu in several stages, and today focuses on a new stage of thermal energy, supporting the offshore oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) operations of national and international companies off the coast of São João da Barra, in the north of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

The project covers logistical support for Brazil’s most extensive stretch of pre-salt oil reserves. As the largest private, deep-water industrial port in Latin America, the Port of Açu also receives 26 million tons of iron ore per year through a mining pipeline of more than 328 km that is part of Anglo-American’s mining operation in the state of Minas Gerais, which is then loaded onto ships and shipped to Asia.

___ Impacts

The construction of the mega-enterprise Porto do Açu, which left 400 small-scale farmers without their land, resulted in unjust expropriations without state compensation. This led to unprecedented violence in the region. <In addition, the environmental impact caused by the port destroyed regional ecosystems known as the Restinga, salinized arable lands, and accelerated coastal erosion processes in an area of recent coastal sediments (Sofatti, 2024).>

The small farmers organized by ASPRIM (Association of Rural and Property Owners of São João da Barra) have, over time, organized actions of resistance and mobilizing their communities against injustices.

Since the morning of April 19, 2017, around 100 farmers from the Açu region, in the municipality of São João da Barra (RJ), have been fighting to reclaim their land, which was expropriated by the Sérgio Cabral government and Eike Batista’s EBX Group. Under the responsibility of the Industrial Development Company of Rio de Janeiro (CODIN), the land was taken from the farmers through an expropriation act and handed over to the LLX company, which sought to establish an industrial district around the Port of Açu.

(Source: Blog do Marcos Pędłowski, https://blogdopedlowski.com/tag/asprim/) Associate Professor at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense in Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, working in the Postgraduate Programs in Social Policies and Ecology and Natural Resources. External Collaborating Researcher at the Center for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Change at the University of Lisbon.

Methodology

The following research was structured based on an understanding of the conflict and its various aspects. First, we identified the theme of the expropriations and the displacement that took place on the 7,036 hectares expropriated. Gradually, these areas were appropriated in order to understand the genesis of the conflict. To do this, it is first necessary to understand the land conflict. Secondly, we focus our attention on two elements that were consequences of the implementation of the Port of Açu Industrial Complex: the large infrastructure built, which includes the extraction of soil from the seabed for the advancement of the port’s central quay with an extension of 12 km inland, and the process of dredging the soil from the seabed, which is then deposited inland. This marine sand residue was placed on agricultural land, directly impacting the water table and water sources, so we investigated two phenomena that were consequences of this impact: soil salinization through the deposit of large tons of removed maritime soil placed in landfills on the mainland and the mega-construction of port infrastructure, such as breakwaters, solid structures that modify the hydro sedimentation of the sea and alter the hydrodynamics of marine currents, causing the acceleration of the erosion phenomenon, present along the entire coast of the Port of Açu, with the greatest impact on nearby localities. Finally, we identified the severe environmental impacts caused by the degradation of natural biomes, environmental reserves, lagoons, springs and streams, modifying the region’s flora and fauna and impacting the restinga.

A restinga is a coastal geographical formation, common in tropical and subtropical areas, characterized by a narrow strip of sandy or clayey land, often covered by dune vegetation, located between the mainland and the sea. It can extend from the edge of the beach to several hundred meters inland, depending on local conditions. Restingas play important roles in protecting the coast from erosion, in maintaining marine and terrestrial biodiversity, and as transition areas between marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

GNA 1 and GNA 2 Thermal Power Plants, implemented at the Port of Açu. 2024. Photograph from the documentary Açu dos Desgostos, Saulo Nicolai ©.

Farmers from the V District of São João da Barra, Since the morning of April 19, 2017, around 100 farmers from the Açu region in the municipality of São João da Barra-RJ, have been fighting to take back their land, which was confiscated by the Sergio Cabral government and Eike Batista’s EBX Group during the camp organized by Asprim in 2017. Pablo Vergara ©.

___ 1. Expropriação

The multimedia investigation focuses on those expropriated and affected by the implementation of CIPA in the municipality of São João da Barra, specifically Água Preta, Campo da Praia and Mato Escuro, where its inhabitants are still resisting the expropriation of their land. In this process, we identified families who have historically lived in the region for three generations, according to the research:

The occupation of the land in the region: More specifically, the settlement of the lands in the studied areas occurred mainly by squatters from the district of Pipeiras, from the town center of São João da Barra, and from neighboring localities belonging to the municipality of Campos dos Goytacazes, such as Córrego Fundo, Azeitona, and Quixaba. (Pires, 2009) Although the occupation of these lands began in the late 19th century, the settlement of areas closer to the Industrial and Port District of Açu dates back to the 1920s and 1940s of the 20th century. Initially composed of large land extensions owned by a few individuals, after the death of some owners, their heirs began a process of subdivision and sale of the lands into smaller lots in the Açu region. (Pires, 2009) However, despite this subdivision, land concentration in São João da Barra remained significant — a fact that Pires (2009) considers a key factor in the EBX Group’s decision to choose the region for the construction of CIPA, in addition to its location.

(Source: https://uenf.br/posgraduacao/politicas-sociais/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2015/06/FELIPE-MEDEIROS-ALVARENGA.pdf)

The expropriation of land in the port of Açu took place gradually. Initially, the ELX company, run by tycoon Eike Batista, acquired some symbolic farms in the region, such as the Caruaru farm, which are considerably large within the territory. The CIPA (Açu Industrial Port Complex) project progressed as its legal-administrative status was consolidated. As the political negotiations progressed in conjunction with the main powers of the state, legislative and legal powers, including the actions of the then governor: Sérgio Cabral (imprisoned for corruption), together with local governments, especially the municipality of São João da Barra, they reached what would be the cornerstone of the conflict. The decree that would modify the regulatory plan for the land where the port of Açu would be located to change the land use to industrial was issued on December 31, 2008. “The occupation of the area that would become the CIPA industrial complex used only 13% of what was projected in the last period. A total of 7,036 hectares were sparsely used, with only 940 hectares, or 87% of the expropriated land, remaining abandoned.”

(Source: Costa, Barcelos, Pag 189. Traces, ruins and resistance: a decade of socio-environmental conflict at the Açu Industrial Port Complex (CIPA), São João da Barra, Rio de Janeiro 2018)

The interviews

The interviews conducted on the subject of land expropriations are relevant according to the degree of state violence exercised. There are two cases of post-expropriation deaths that farmers refer to as “heartbreak”, “dying of heartbreak” after expropriation. These are common events in the region where families have lived on the land for more than 150 years.

A pineapple farmer, on the day of the funeral of his father, Don José Irineu Toledo, his land was violently expropriated. It is one of the most emblematic cases of public-private violence. Adeilson talks about his stress, a painful memory of his father’s death, a deep depression and suffers from “Disgust” according to his own account.

Listen to the interview:

A small regional farmer, he produces a variety of agricultural crops and has a wealth of folk wisdom and ancestral knowledge of edible and inedible plants.

Listen to the interview:

Professor of sociology at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, whose research laboratory has produced a dozen tests on socio-environmental conflicts. One of the researchers who has produced the most material on the conflict has an audiovisual archive made available for use. BA and MA in Geography from UFRJ and PhD in Environmental Design and Planning from Virginia Tech. Associate Professor at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense in Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, working in the Postgraduate Programs in Social Policies and Ecology and Natural Resources—external Collaborating Researcher at the Center for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Change at the University of Lisbon.

Listen to the interview:

___ 2. Salinization

(Source: https://uenf.br/posgraduacao/ecologia-recursosnaturais/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2013/10/2016-mestrado-UENF-Juliana-Ribeiro-Latini.pdf)

At the end of 2012, researchers from the Environmental Sciences Laboratory at UENF collected water samples at various points in the 5th District of São João da Barra, at the request of local farmers who suspected changes in the quality of the water on their properties. The results indicated that the waters of the Quitingute Canal and other water bodies showed high salinity levels, which were linked to the construction of the hydraulic embankment of CIPA. Farmers also reported significant crop losses, associating them with the increased salinity of irrigation water.

Several studies confirmed that the waters of the Quitingute Canal were indeed salinized, reaching conductivity levels of up to 42,000 µS/cm between November and December 2012 (IFF, 2013). According to the State Department of Environment of Rio de Janeiro, OSX was fined R$ 1.3 million and was required to implement mitigation measures in the Lagoa do Açu State Park area, as well as to dredge three points in the Quitingute Canal to assist in water flow reduction and salinity mitigation. Despite these measures, it is known that new environmental damage investigations have been reopened regarding the 2012 salinization event. More recently, the Public Prosecutor’s Office opposed OSX’s request to terminate the damage repair process, arguing that reparation must consider the entire area of the 5th District of São João da Barra.

Interviews:

Farmer directly affected by the salinization of his crops. Resident of the 5th district of São João da Barra.

Listen to the interview:

Community and regional leader and small farmer, recently nominated to receive Rio de Janeiro’s highest honor, the Tiradentes Medal. Dona Noemia is a crucial player in the conflict. She knows all the stories and has been a spokesperson for the small farmers.

Listen to the interview:

Director of the Fluminense Federal University, researcher of the conflict, with a doctorate in agrarian and socio-environmental conflict in the port of Açu.

Listen to the interview:

Professor of sociology at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, whose research laboratory has produced a dozen tests on socio-environmental conflicts. One of the researchers who has produced the most material on the conflict has an audiovisual archive made available for use. BA and MA in Geography from UFRJ and PhD in Environmental Design and Planning from Virginia Tech. Associate Professor at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense in Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, working in the Postgraduate Programs in Social Policies and Ecology and Natural Resources—external Collaborating Researcher at the Center for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Change at the University of Lisbon.

Listen to the interview:

The locality of Barra do Açu is affected by the coastal advance caused by the intervention of port infrastructures, the Breakwater, a concrete and stone structure that enters the sea, modifying coastal hydro-sedimentation. 2023, Pablo Vergara ©.

___ 3. Erosion

(Source: https://uenf.br/posgraduacao/ecologia-recursosnaturais/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2013/10/2016-mestrado-UENF-Juliana-Ribeiro-Latini.pdf)

Interviews:

A resident of Barra do Açu, hit by erosion.

Listen to the interview:

Community and regional leader and small farmer, recently nominated to receive Rio de Janeiro’s highest honor, the Tiradentes Medal. Dona Noemia is a crucial player in the conflict. She knows all the stories and has been a spokesperson for the small farmers.

Listen to the interview:

Professor of sociology at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, whose research laboratory has produced a dozen tests on socio-environmental conflicts. One of the researchers who has produced the most material on the conflict has an audiovisual archive made available for use. BA and MA in Geography from UFRJ and PhD in Environmental Design and Planning from Virginia Tech. Associate Professor at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense in Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, working in the Postgraduate Programs in Social Policies and Ecology and Natural Resources—external Collaborating Researcher at the Center for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Change at the University of Lisbon.

Listen to the interview:

___ 4. Environmental Impact

In addition to the criticisms already mentioned in relation to the expropriation process, another point of controversy related to the implementation of CIPA concerns the licensing process and the assessments carried out to give the green light to the project. The decision to conduct the licensing of each CIPA project individually was criticized, as this fragmented approach was interpreted as a deliberate strategy by the Rio de Janeiro government to facilitate their approval. Another point of disagreement was the competence attributed to INEA to carry out licensing, since, given the location of the project, IBAMA would be the most appropriate licensing body.

(Source: https://uenf.br/posgraduacao/ecologia-recursosnaturais/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2013/10/2016-mestrado-UENF-Juliana-Ribeiro-Latini.pdf)

Interviews:

Community and regional leader and small farmer, recently nominated to receive Rio de Janeiro’s highest honor, the Tiradentes Medal. Dona Noemia is a crucial player in the conflict. She knows all the stories and has been a spokesperson for the small farmers.

Listen to the interview:

Director of the Fluminense Federal University, researcher of the conflict, with a doctorate in agrarian and socio-environmental conflict in the port of Açu.

Listen to the interview:

Professor of sociology at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, whose research laboratory has produced a dozen tests on socio-environmental conflicts. One of the researchers who has produced the most material on the conflict has an audiovisual archive made available for use. BA and MA in Geography from UFRJ and PhD in Environmental Design and Planning from Virginia Tech. Associate Professor at the Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense in Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, working in the Postgraduate Programs in Social Policies and Ecology and Natural Resources—external Collaborating Researcher at the Center for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Change at the University of Lisbon.

Listen to the interview: